Divine Provenance

To our good fortune, Aristotle did not write, "It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it," because this quotation, by sociologist Lowell L. Bennion from a mistranslation of Aristotle, offers many lessons. Its dodgy pedigree makes it no less insightful, judging by how often it gets cited. Does it even require attribution, as many old sayings do not? Probably yes–it dates only to 1989 (the year the Berlin Wall fell), in Bennion’s book “Religion and the Pursuit of Truth”. While some of us remember the Berlin Wall, few are going to recall Bennion’s name, let alone the misquotation’s context in his book. It is simpler to remember the author as “Not Aristotle”.

Then there are cases of viral false factoids. Often the author is unknown, as in the case of “We only use 10% of our brains" and “We lose 80% of body heat through our heads”. Sometimes a false factoid’s author is actually known, such when a former Google CEO commented about data production:

“There were 5 exabytes of information created between the dawn of civilization through 2003, but that much information is now created every 2 days.” ~ Eric Schmidt

Spread round and round, these unfacts refuse to die, despite any amount of refutation.

Some falsehoods attain the status of common knowledge in a phenomenon known as the Mandela Effect. Paranormal researcher Fiona Broome reported that hundreds of people remembered Nelson Mandela dying in prison in the 1980s, when he not only survived but went on to become president of South Africa. Given Mandela’s heroism and fame, it is strange that the effect bearing his name would be such an odd one. It was even the theme of a 2019 movie, The Mandela Effect, which explored Broome’s theory that alternative memories might come from intersecting parallel realities—multiple versions of truth co-existing, like Schrödinger’s cat. More likely, such beliefs merely originate in the quantum foam of the infosphere, ex nihilo fit, with the more viral memes taking on life, like Hawking radiation. Call them Hawking memes.

Less amusing is the corruption of entire information sources. The bigger and more popular the source, the greater the incentive to hijack it. So is also, presumably, the incentive to defend it, but that defense may pose a coordination problem if the source is a public good. In many cases, there will be more people interested in skewing or even falsifying information than sentinels trying to maintain its integrity. Wikipedia is a classic example.

“Wikipedia was and is inherently susceptible to ideological capture. This isn't a problem that will be solved within the scope of an information architecture that collapses vehemently held and diametrically opposed points of view into a single small text box.” –Arto Bendiken

Corruption discourages information contribution: why provide information to a repository if it is likely to be corrupted, and which consumers will trust and value less?

What is to be done about misinformation, some of which, despite or even because of its flaws, is valuable? How to give credit or shame where they are due? And what is to be done today, when AIs create and operate independently on data, able to mitigate or exacerbate the problem?

For some guiding principles, we might look to Isaac Asimov, who introduced the Three Laws of Robotics. Asimov assumed inherently rational robots, and did not even mention any rationality principles among his Three Laws: what would he say about today’s hallucinating AIs’ interaction with an increasingly polluted infosphere? Is the alternative to the information jungle a set of walled gardens, like Asimov’s planet Aurora, where humans interacted only with a trusted few?

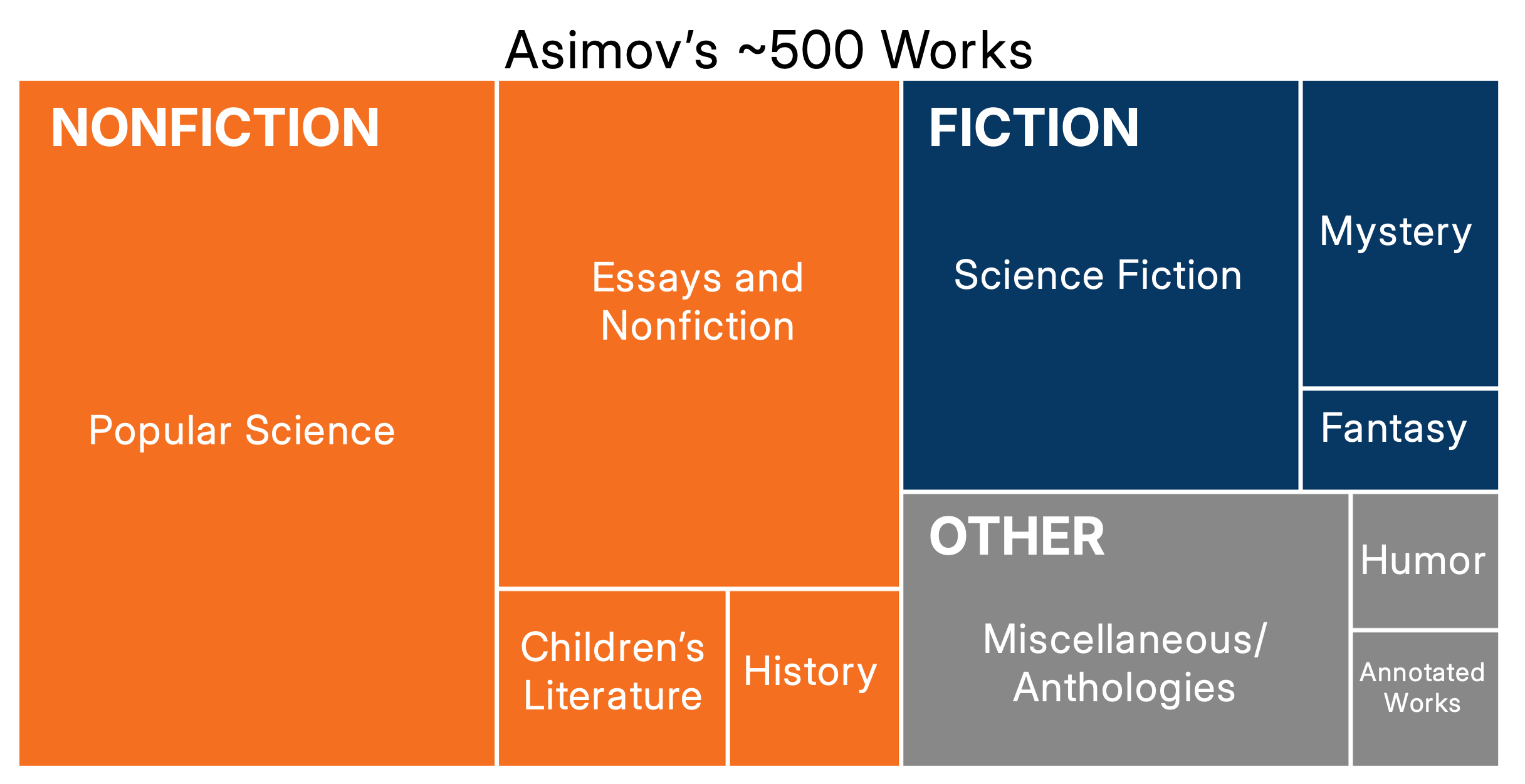

We remember Isaac Asimov for his science fiction, but F&SF was only about a fifth of the roughly 500 works that he wrote or edited. The bulk of Asimov’s publications was popular science. Though Asimov was a professor of biochemistry, and loved science, he was not a practicing scientist himself: he was an explainer. However, he did more than explain other people’s ideas–he had his own ideas and principles, which he championed.

From Asimov’s vast body of works we can distill seven values, grouped in two categories—rationality and ethics—resulting in one fundamental value:

That final value is today often called techno-optimism, and it sums up Asimov pretty well. Asimov’s novels did not portray utopias free of evil, but reason and technology prevail.

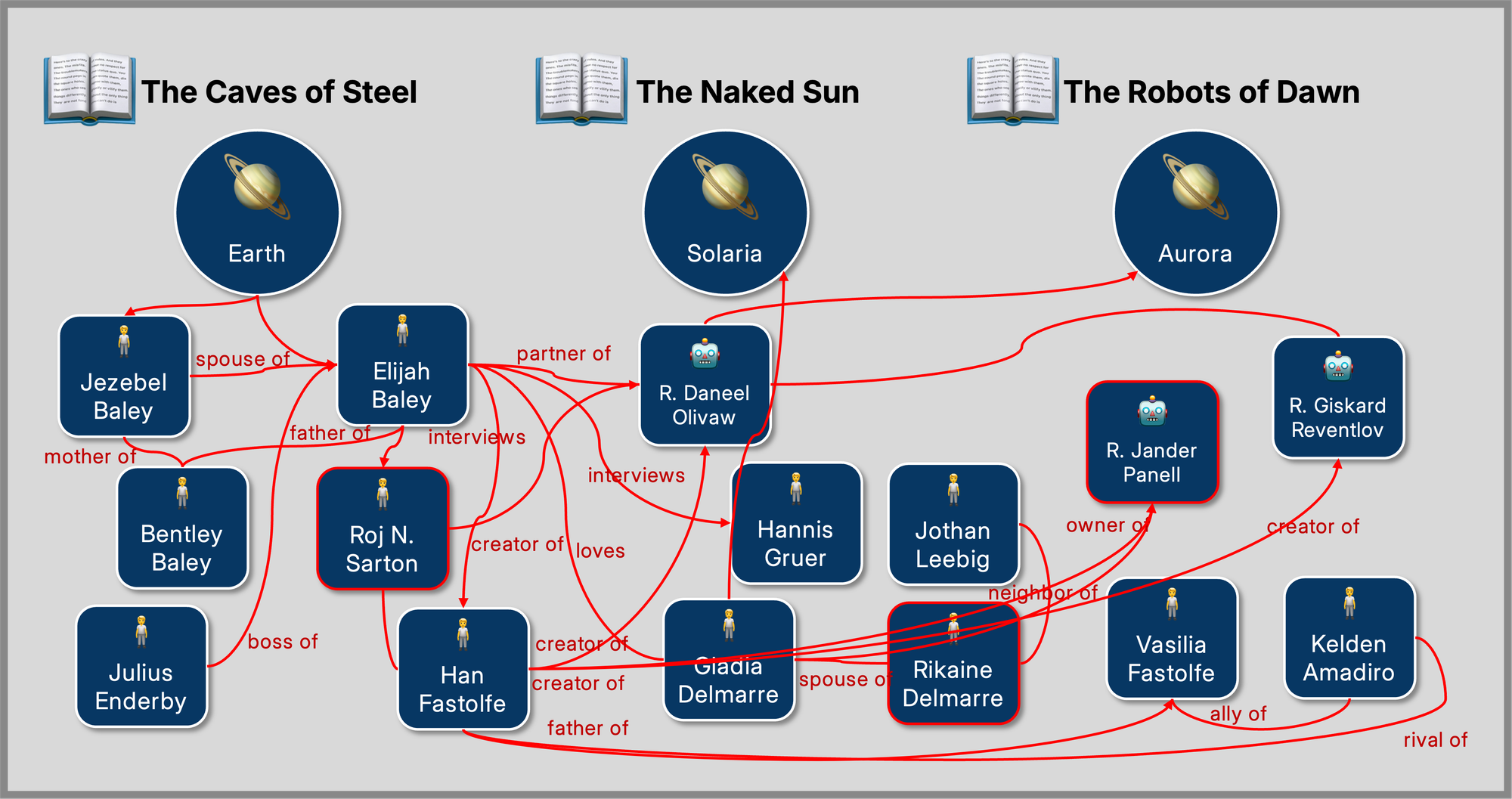

Asimov’s Robot Novels illustrate his values, and suggest a technique for coping with large amounts of information of varying quality. The Robot Novels are whodunnit detective stories, combining the sci-fi and mystery genres. The detective partners had to keep in their brains, wet or positronic, myriad facts and alternate hypotheses, some contradictory.

The key to not getting lost in an information jungle is remembering the connections among entities. Detectives often maintain an evidence board, a knowledge graph of people, leads, and theories. Such “murder maps” or relationship charts are a famous film trope.

Of particular importance is one type of relation: provenance—traceability of information’s origins. Information is worth less without a source reference. In the case of a crime investigation, giving false evidence is itself evidence. However, provenance adds a dimension to information complexity, greatly increasing the cognitive load. Provenance is difficult to maintain without computational support, especially in the modern world, with vastly more human relationships and information sources than our brains were designed for.

Humans already need computational augmentation, in one form or another, and that is certain to increase. The Robot Novels’ human detective, Elijah Baley, was fortunate to have a robot partner, R. Daneel Olivaw, with better memory.

Each of the Robot Novels had a murder victim (a robot, Daneel’s twin Jander, in the third book), and numerous witnesses and suspects to be questioned. Some were incentivized to lie. In data markets, provenance enables accountability, for rewarding contributors of good information and punishing polluters. A structured data market supports other ecosystem niches: infomediaries such as verifiers (e.g., fact-checkers) and curators. We need a systemic solution, and one will certainly emerge.

"Web3 AI is sparking hope for a trustless, decentralized future where cognitive clarity reigns." –Talal Thabet

In the Biblical parable “The Wise and Foolish Builders,” the wise man builds his house on rock, while the foolish man builds on sand. In the modern version, the wise man builds on knowledge (justified belief), while the foolish man builds on falsehood. In the Misinformation Age, robust architectures as well as individual agency will need technological epistemic support.

“A post-Wikipedia encyclopedia will not enforce a single narrative, but rather support any plurality of perspectives and narratives that may differ even on epistemic and/or ontological grounds. An epistemic superposition, if you will. Reconciliation into a simplified single narrative will still be possible, using machine intelligence to collapse the superposition and stitch it into linear form. If it is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it, higher education will increasingly consist of perceiving and examining the superposition. A post-Wikipedia encyclopedia will deploy a combination of mechanism design and machine intelligence built on top of a permissionless knowledge architecture that doesn't gatekeep who can edit what, but instead uses info finance to incentivize and signal boost quality contributions.” –Arto Bendiken